Giving Every Child a Voice: Why Communication Boards Belong in Playgrounds

As a BCBA, one of the most powerful things I see every day is how communication opens doors. It is not just about words; it is about being seen, heard, and understood. For many children, especially those with speech or language differences, those doors do not always open easily. And on playgrounds, the very places where kids should be free to connect, laugh, and play, that gap can feel even wider.

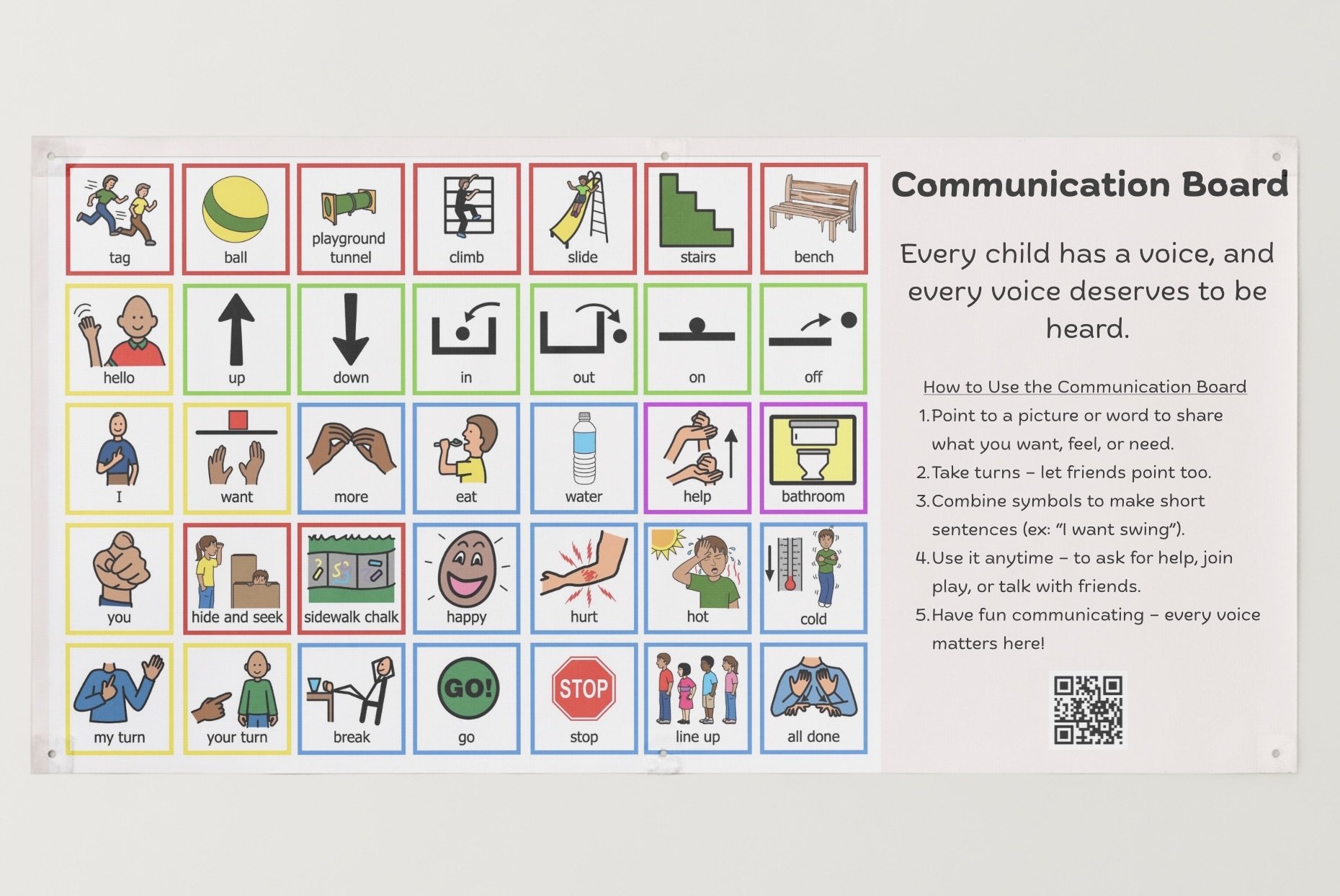

That is where communication boards come in. Imagine a child at the playground who wants to say, “Your turn!” or “Let’s play!” but the words just will not come. A communication board gives that child another way to share their voice by pointing to pictures and symbols that show what they want to say.

Why Play + Communication Go Hand in Hand

Play is more than fun; it is how kids learn. Through games of chase, turns on the slide, or even building in the sandbox, children practice problem-solving, sharing, and making friends (Ginsburg, 2007). But when communication is hard, those same moments can turn into frustration or isolation.

Visual supports, like communication boards, change that. Research shows that augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools give children more opportunities to participate and reduce barriers to inclusion (Light & McNaughton, 2012; Romski & Sevcik, 2005).

The Big Benefits of Communication Boards

Here is what I see when communication boards are available on playgrounds:

Inclusion: Every child has a way to join in, whether they use words, gestures, or pictures.

Confidence: Kids feel empowered when they can make their needs known without someone speaking for them.

Friendship Skills: Peers learn to pause, listen, and respond, which builds patience, empathy, and understanding (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013).

Independence: Children can ask for help, join a game, or share ideas in their own way.

Language Growth: Visual symbols reinforce vocabulary and communication for all children, not just those with speech delays (Hart & Risley, 1995).

Why Visuals Work

Pictures make language concrete. When kids see an image of “swing” or “help,” the meaning is clear right away. Visuals support children with autism, multilingual learners, and kids still developing language (Ganz et al., 2012). They also give kids more ways to succeed and less pressure to “get the words right.”

A Community Vision

My dream is simple: to see communication boards installed in every local playground so no child is left without a voice. Communities can make this happen by:

Working with families and professionals to design boards that meet real needs.

Partnering with schools, PTAs, and local parks departments for funding and installation.

Choosing words that fit playground life, like swing, run, stop, help, and friend.

Encouraging everyone, kids, parents, and siblings, to use the boards so they become part of the culture.

Final Thoughts

Playgrounds should be places where all children belong. By adding communication boards, we are not just giving kids a tool. We are teaching them, and their peers, that communication takes many forms, and every single one matters.

Every child deserves the chance to laugh, play, and connect. Communication boards make that possible.

Sources for Parents Who Want to Learn More

Ginsburg, K. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191.

Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2012). Supporting the communication, language, and literacy development of children with complex communication needs. Assistive Technology, 24(1), 34–44.

Romski, M., & Sevcik, R. (2005). Augmentative communication and early intervention: Myths and realities. Infants & Young Children, 18(3), 174–185.

Beukelman, D. & Mirenda, P. (2013). Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Paul H. Brookes.

Hart, B. & Risley, T. (1995). Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Paul H. Brookes.

Ganz, J. et al. (2012). A meta-analysis of aided augmentative and alternative communication with individuals with autism. JADD, 42(1), 60–74.